Negotiating with the Harvard Method

Finally gaining the upper hand in negotiations.

Negotiating with the Harvard Method

Everyone has done it at some point. With friends, acquaintances, strangers, even with their own parents. You might have guessed it: we're talking about negotiating.

In this article, we'll look at a successful negotiation example and apply the Harvard Method.

Why Negotiate?

Whether as kids negotiating bedtime, as new drivers haggling over our first car price, or as purchasing managers discussing supplier terms. We always aim to get the best deal possible. Why settle for less than we can get?

A Thought Experiment

Let's take the last example. We're part of a company's purchasing department negotiating terms with a new parts supplier for a partnership contract. We want to buy as much as possible for the lowest price to produce cheaply and increase profit margins. This involves an order for a pilot series of 500 units and potential future contracts for new products. The new supplier currently only knows about the 500 units.

Unfortunately, our parts supplier has a similar goal. They want the best terms for themselves and aim for a high price to achieve good revenue and profit.

This creates a conflict of interest, and both parties try to find a solution. Let's explore two possible solutions.

Option 1

Each party only sees their own problem in the conflict. The supplier refuses to go below €50/unit and sticks to their price position.

Our purchasing team has set a limit at €20/unit, which they fiercely defend.

There's haggling, threats, and maybe even insults. Yet, both parties can't agree because they cling to their set goals, price expectations, and desired outcomes.

Disheartened, our department looks for a more "understanding" partner...

The Core of the Harvard Method

Roger Fisher and William Ury were professors at Harvard Law School and co-founders of the Harvard Negotiation Project. They developed the Harvard Method and published the book "Getting to YES" in 1981, known in German-speaking regions as "The Harvard Method," a standard work on negotiation methods.

Let's first look at the book's core messages before trying to solve our problem using the Harvard Method.

1. Separate the People from the Problem

This means being aware that in a negotiation, you're not just discussing an issue but also working on the relationship with your negotiation partner. To maintain a profitable partnership, the negotiation result should be seen as a joint solution to a shared problem, not targeting the partner as the problem.

Try to understand why your partner holds their position while clearly stating your own. Here, objectivity and clarity are key. A friendly and respectful approach can help find alternative solutions together. "Be hard on the problem, soft on the people," the book advises.

2. Focus on Interests, Not Positions

To avoid being limited in solutions, negotiate your interests, not your position. The position is, for example, a price or quantity, the "what" of the negotiation. The interest reveals the reason for your actions, the "why" behind them.

Be open about your interests and ask about your partner's. This fosters empathy and reduces conflict potential.

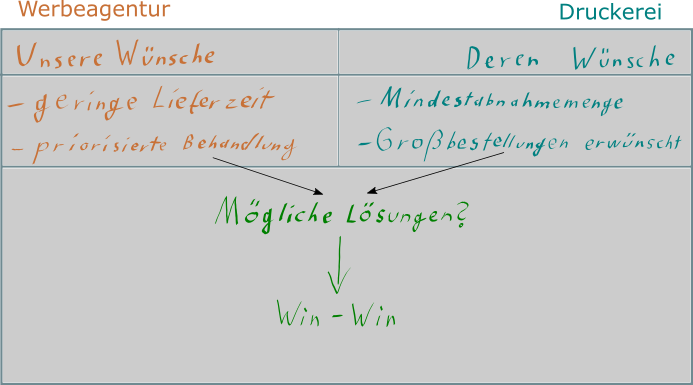

3. Develop Options for Mutual Gain

You don't have to agree on one solution immediately. Explore multiple options together. A brainstorming session can help gather all wishes. Then, consider how to combine both parties' wishes in different ways.

This way, you have a good chance of finding an agreement that satisfies both sides, creating a win-win situation. This is what the Harvard Method aims for in negotiations.

4. Use Objective Criteria

To avoid damaging haggling over cents, use widely accepted objective standards instead of personal feelings when weighing arguments or valuing wishes. These include:

- Market comparisons

- Independent appraisals

- Standards

- Legal regulations

- An impartial mediator

These standards' objectivity increases acceptance and the sense of fairness in a solution.

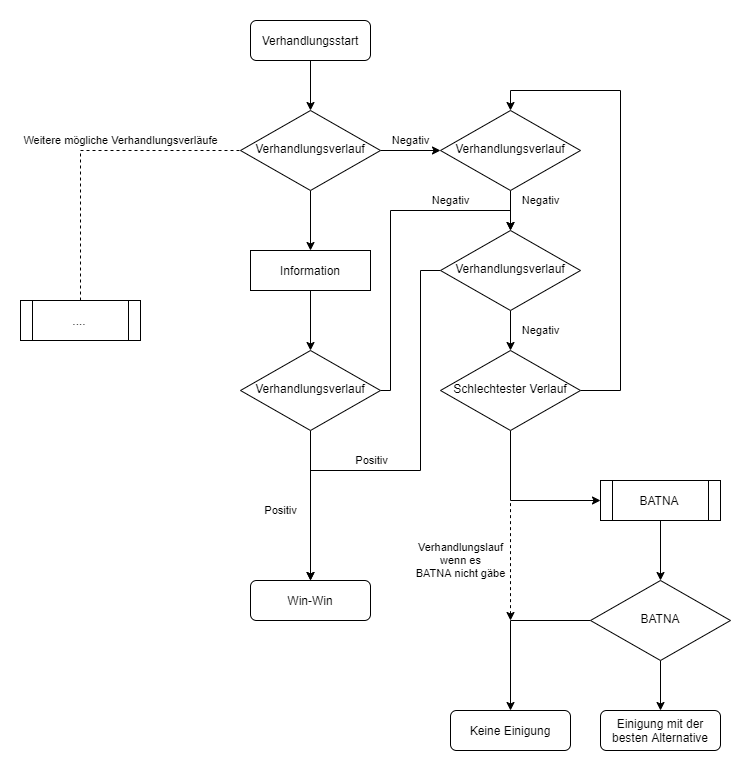

If All Else Fails

What if the negotiation partner doesn't cooperate? Cold businesspeople who won't budge or stubborn individuals exist everywhere. If you can't find a good agreement, know your limits. The Harvard Method offers a last resort, the BATNA.

BATNA stands for "Best Alternative To Negotiated Agreement."

Before negotiations, consider one or more alternatives if you can't reach an agreement. This boosts confidence and, if needed, shows professionalism.

Use your BATNA if you feel the negotiation results are worse than your BATNA. But remember, your counterpart might also have a BATNA.

Example - Option 2

Let's revisit our example using the Harvard Method.

In Option 1, the focus was on the €20/unit price. Our real interest is finding a reliable supplier who prioritizes us for urgent orders.

Before negotiation day, our department agrees on a BATNA: If the supplier isn't interested in a long-term partnership or seems unreliable, we'll offer €32/unit for this order and a second order for another project with higher margins for the supplier.

The negotiation begins. The supplier's salesperson is warmly greeted by three of our team members with coffee or tea and asked about their journey. We share our interest in finding a partner for our new product line. We stress that we're budget-constrained for this project, which isn't usually the case. As we're close to production, we ask if delivery of 500 units in three weeks is possible if we agree.

The salesperson replies that this would require significant effort and a surcharge for the short timeframe. They quote €50/unit.

We're surprised by this, as we've checked market prices for our parts, but we avoid haggling. We ask why the price is so high and if the surcharge is necessary.

We learn that the supplier's production management is busy planning a new production line due to a new hall being built. Thus, production management is limited.

As this suggests increased production capacity, we ask if the new line's capacity is already planned. We learn it's only 40% booked.

We then reveal that we have other product lines in planning and could source parts from them, promising further contracts if they accommodate us on price and delivery time for this project. To start production, 200 units in two weeks would suffice, with the remaining 300 needed later.

Unfortunately, the salesperson needs something more concrete. We offer not only this order but a cooperation contract for a long-term partnership, benefiting both companies. This piques the salesperson's interest, as they're tasked with finding more customers for the new production capacity.

The contract would prioritize our orders, even for urgent prototype orders, while ensuring long-term profits and work for the supplier. The condition is successfully delivering the current order of 200 parts in three weeks and the remaining 300 within two weeks.

We agree on €28/unit and schedule a meeting to discuss a cooperation contract.

Conclusion

This fictional negotiation shows the value of understanding the reasons and interests of your negotiation partner. We treated the salesperson kindly and engaged with their problem. We avoided direct position negotiation by exploring interests and found a solution for both sides. We used the cooperation contract, a well-known tool, to reach an objectively fair agreement.

We were lucky the salesperson was accommodating, and we didn't need our BATNA. But this was a relatively simple negotiation. Don't you think?