6 Steps to Decision

A guide to making meaningful decisions

6 Steps to Decision

Every day, we make thousands of decisions. Most of these are unconscious. These are mostly everyday decisions:

- Coffee or tea?

- The black or the brown shoes?

- Do I go left or right?

- ...

However, we make big decisions consciously. These require time and effort because they significantly impact our lives. They shouldn't be made just "by gut feeling" or purely rationally.

- Career choice

- Partner choice

- Desire for children

- ...

Evaluating Decisions

The outcome is not what determines the quality of a decision.

Good Decisions Can Have Bad Outcomes.

Imagine I forgot an important appointment. If I take the next train, I'll arrive stressed, five minutes before it starts (if the train is on time). Google Maps says I'll get there 30 minutes earlier if I drive. So, I decide to drive. Unfortunately, there's a rear-end collision because another driver doesn't see my brake lights. Of course, I miss the appointment. Still, it was the right decision to drive instead of taking the train.

This clearly shows that bad luck can affect the outcome of my decision. But the quality of my decision remains the same.

Bad Decisions Can Have Good Outcomes.

On the other hand, let's say I choose the train. It's delayed, and I miss my appointment. However, I find a 100-euro bill under my seat. Was it a good decision to take the train? It remains a bad decision.

So, it's important to evaluate a decision based on its quality and whether it was made thoughtfully, not just on the outcome.

Combining Head and Gut

Important decisions require both experience and intuition, as well as rational consideration. When both factors are included, these are called reflective decisions.

Head decisions are demanding for our brain. Our gut feeling allows quick decisions, incorporating our experiences and personal well-being. However, we can't rely solely on gut feelings.

Cognitive Biases

The problem with gut decisions is they're prone to errors. We often fall victim to several cognitive biases.

Availability Heuristic

This bias causes us to overvalue experiences or recent events because they're readily available.

Example: The last three times I took the bus, it was late. So, I drive. We use the easily available link bus = late, ignoring the many buses that are on time every day.

Another example: Recently, there have been frequent reports of train accidents. So, I avoid trains. Based on recent events, we link trains with accidents, ignoring the many safe trains.

Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is why we often stick to the status quo, even if we're unhappy. We weigh losses more heavily than gains; we prefer to keep an unhappy situation rather than risk losing it for a potential gain (well-being).

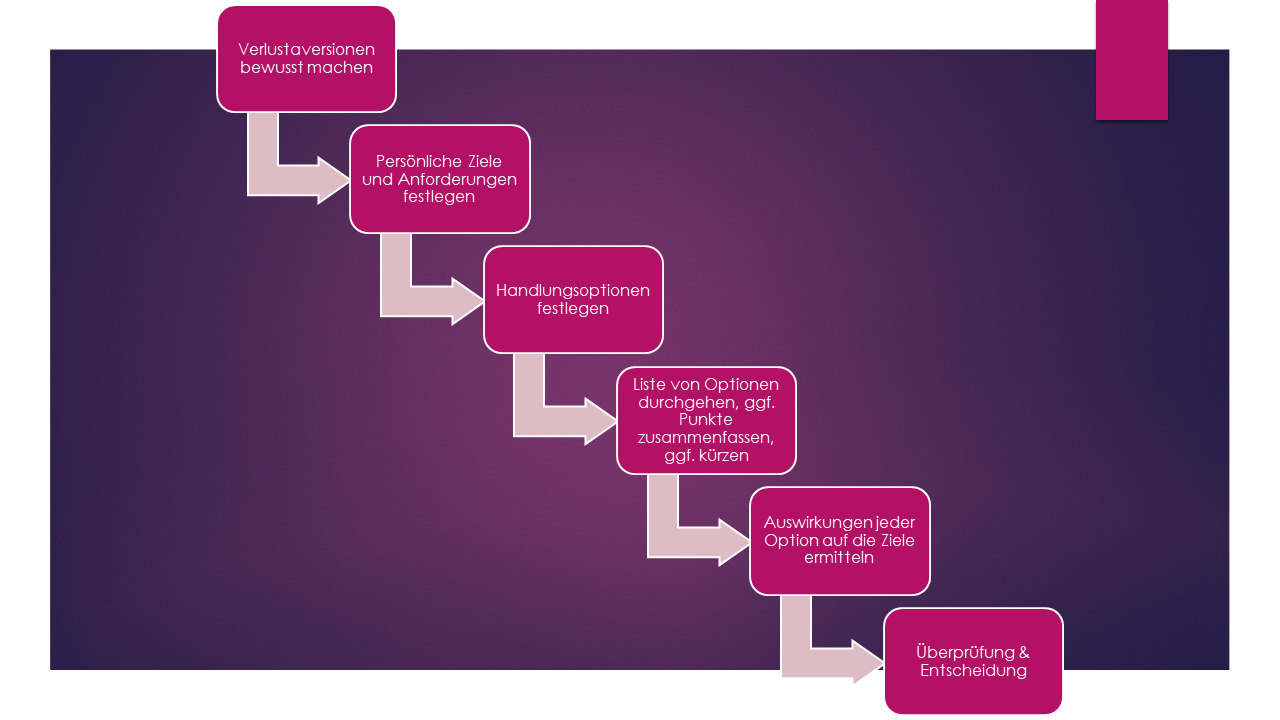

The Path to a Reflective Decision

1. Recognize Loss Aversions

First, become aware of your loss aversions. Understand that change processes often initially cause discomfort. By making reflective decisions, you do a lot to meet desired goals and requirements.

Tina is a project manager at a large energy company. For nearly a year, she feels stuck in her job. She hasn't yet changed her situation, mainly due to loss aversion, like many in her position.

Tina needs to recognize her loss aversions to take action.

2. Define Personal Goals and Requirements

This step involves becoming aware of the goals you want to achieve with the change. Tina asks herself, "What is truly important to me?"

Tina feels stuck in her current job. She wants to earn more to pursue her expensive hobby—skydiving. She also wishes to work more in climate protection. Flexibility and home office are important to her, so she can be there for her kids after school. Tina prioritizes her goals and requirements:

- Flexibility

- Work focused on climate protection

- Higher income

3. Identify Options

This step involves identifying the possibilities Tina has to achieve her goals. A bird's-eye view often helps to find less obvious options.

Tina could apply to a competing energy provider with an open "Head of Renewable Energy" position.

She could also discuss with her boss her interest in leading the "North Sea Wind Farm" project.

Tina could start her own business, offering consulting and project management services on climate protection.

4. Review and Possibly Combine or Shorten Options

Next, consider if options can be combined or shortened if there are more than a handful.

5. Assess Each Option's Impact on Goals

Self-employment initially offers flexible scheduling. However, Tina would often need to visit clients, limiting time with her kids after school. So, this option is out.

Applying for "Head of Renewable Energy" would bring more money and purpose. She'd work from home four days a week. But core hours until 5 PM mean less time with her kids. The high responsibility means more work than now.

Leading the "North Sea Wind Farm" project means working in climate protection. But she could work from home only two days a week after training. A salary increase isn't expected now.

6. Review & Decide

Here, gut feeling comes back into play. Tina values her work environment highly. She's happy with it at her current company. She feels uneasy about not seeing her colleagues anymore. So, she chooses the wind farm project at her current company, even though rationally, the best decision would be the head position.

The key here is: The more the head was involved in previous steps, the more it's time to consult the gut. A decision should only be made when both head and gut are involved.

Summary & Conclusion

For the "big" decisions in life, consult both your head and gut. In the decision process, recognize loss aversion, define personal goals, requirements, and values, identify options from a bird's-eye view, and check against defined goals and values. Finally, ensure harmony between head and gut feeling.